Letters in Focus: Things That Go Bump in the Night

Tags: Archives, Bodleian Resources, England, Ghosts, History of Scholarship, Letters in Focus, Libraries, News, Religion, Seventeenth Century, Union Catalogue, Witchcraft

So, the evenings draw in, All Hallows’ Eve is upon us, and I find myself creeping through autumnal mists to the Bodleian’s Special Collections in search of ghosts.

There are many fleeting glimpses of hauntings in EMLO. In 1675, William Fulman asked Anthony Wood to confirm ‘the story of a ghostly funeral procession at night to St Peter le Bailey which terrified some of the Masters who were walking with the Proctor, but two which followed the procession to the Church door found the doors to open of their own accord, and then all to vanish and are since dead’. In 1706, Anne Griggs reported ‘the ghostly interview at Souldern Vicarage between the Vicar Mr Shaw and the apparition of his friend Mr Naylor on July 28… The apparition foretells the death of Mr Shaw…’ (sadly, Mr Naylor was a well-informed ghost; the Clergy of the Church of England Database [Person ID: 20286] reveals that one Geoffrey Shaw, rector of Soulderne, Oxfordshire, died on 17 November 1706, less than four months after this ghoulish encounter).

|

|

|

|

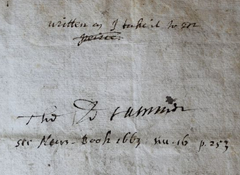

Bodleian Library, MS Ballard 1, fols 72–73: A seventeenth-century poltergeist. Images reproduced courtesy of the Bodleian Libraries.

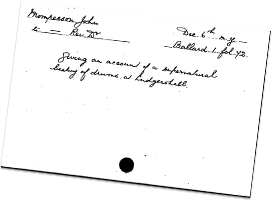

One record above all others tempts me out into the damp October fog: on a handwritten index card from the Bodleian card catalogue that gives no year, and describes a John Mompesson writing to a Reverend Doctor (now known to be William Creed, Oxford’s Regius Professor of Divinity) on 6 December (now known to be 1662), are the words ‘supernatural beating of drums’. Calling up the letter, I encounter a spine-chilling tale of a seventeenth-century household terrorized by a poltergeist. Mompesson describes how, following his apprehension of a fraudulent drummer in Ludgershall (Wiltshire) and the confiscation of the latter’s instrument, his family home in nearby Tedworth (now Tidworth) was assailed by nocturnal thumps and noises so extreme that ‘the windows would shake and the beds’. His children were special targets; apart from a brief interlude of three weeks after his wife gave birth, their beds were beaten, and the family had to endure the tune ‘Roundheads and Cuckolds goe digge, goe digge’ (more on this popular early modern ditty here). Whatever ‘it’ was ran ‘under the bed-teeke’ and scratched as if it had ‘iron talons’, tossing the young ones in bed; it left sulphurous smells, it hurled shoes over the heads of adults, pulled the infants by their nightgowns and hair, and even threw a bedstaff at the rector of Tedworth, John Cragge (CCED Person ID: 21834, yet another cleric who died relatively soon after his brush with the supernatural). See the letter images above for the whole terrifying story.

One record above all others tempts me out into the damp October fog: on a handwritten index card from the Bodleian card catalogue that gives no year, and describes a John Mompesson writing to a Reverend Doctor (now known to be William Creed, Oxford’s Regius Professor of Divinity) on 6 December (now known to be 1662), are the words ‘supernatural beating of drums’. Calling up the letter, I encounter a spine-chilling tale of a seventeenth-century household terrorized by a poltergeist. Mompesson describes how, following his apprehension of a fraudulent drummer in Ludgershall (Wiltshire) and the confiscation of the latter’s instrument, his family home in nearby Tedworth (now Tidworth) was assailed by nocturnal thumps and noises so extreme that ‘the windows would shake and the beds’. His children were special targets; apart from a brief interlude of three weeks after his wife gave birth, their beds were beaten, and the family had to endure the tune ‘Roundheads and Cuckolds goe digge, goe digge’ (more on this popular early modern ditty here). Whatever ‘it’ was ran ‘under the bed-teeke’ and scratched as if it had ‘iron talons’, tossing the young ones in bed; it left sulphurous smells, it hurled shoes over the heads of adults, pulled the infants by their nightgowns and hair, and even threw a bedstaff at the rector of Tedworth, John Cragge (CCED Person ID: 21834, yet another cleric who died relatively soon after his brush with the supernatural). See the letter images above for the whole terrifying story.

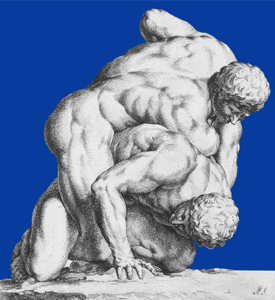

A demonic representation of the Tedworth drummer from Glanvill’s 1681 treatise

Endorsements on the letter, including a cross-reference to a 1663 news book

The Drummer of Tedworth, it turns out, is a celebrated case within the historiography of witchcraft and the early modern occult; it was given a central place in Joseph Glanvill’s 1681 attack on scepticism, the Saducismus Triumphatus, its notoriety continued to grow in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and it has even been subject to minor Disneyfication. The incident, its manuscript witnesses, and its complex appropriation and memorialisation by and within different intellectual traditions is analysed in detail in a 2005 article (pdf) by Michael Hunter, which includes a full transcription of this same 6 December letter collated from three known extant versions: a copy in Corpus Christi, Oxford; a now untraceable copy formerly in a private collection in Dorset; and a copy in the hand of Anthony Wood. The document thrown up by our cryptic Bodleian card record is almost certainly not Mompesson’s original letter – there is no seal, and the lines extending to the page edges on both sides of the folio are indicative of copying – but rather adds a fourth scribal copy into the mix, one that, judging by the endorsements in two separate hands, enjoyed a complex afterlife before becoming part of the Ballard collection, most likely via the papers of Arthur Charlett (on the scribal publication and circulation of newsworthy missives in early modern England see chapter seven of James Daybell’s recent monograph on the material letter and his podcast in our 2011 seminar series). Even if this account is second-hand, close the curtains, pull up a chair, and get reading; there’s nothing like a percussive poltergeist to add drama and intrigue to Halloween…

Letters in Focus with Miranda Lewis

Miranda is editing metadata from the Bodleian card catalogue of correspondence for our union catalogue, Early Modern Letters Online. On a regular basis, she brings us hand-picked and contextualised records.

![Caricature, from a South Sea Bubble card. 1720. (Reproduced in Charles Mackay, Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds. [London, 1857], p. 61; image sourced from Wikimedia Commons).](../../wp-content/uploads/2012/07/Bubble_Cards.png) As world economies stagger from one crisis to the next and headlines flip-flop between the Eurozone emergency and the scandal of inter-bank lending rate fixing, EMLO provides valuable historical insights into financial turbulence and the effects of similar bubbles and crashes. We may face fresh causes of fiscal breakdown today, but the boom and bust cycle is far from new.

As world economies stagger from one crisis to the next and headlines flip-flop between the Eurozone emergency and the scandal of inter-bank lending rate fixing, EMLO provides valuable historical insights into financial turbulence and the effects of similar bubbles and crashes. We may face fresh causes of fiscal breakdown today, but the boom and bust cycle is far from new.

With its whirl of bunting, teapots, cotton frocks, and the river pageant, Diamond Jubilee fever is sweeping the country for just the second time in British history. Early modern subjects might not have had the opportunity to celebrate a sixty-year reign, but it’s clear from

With its whirl of bunting, teapots, cotton frocks, and the river pageant, Diamond Jubilee fever is sweeping the country for just the second time in British history. Early modern subjects might not have had the opportunity to celebrate a sixty-year reign, but it’s clear from

Join

Join