* You are viewing Posts Tagged ‘Archives’

Kim McLean-Fiander

May 13, 2012

Events, Lectures, Podcasts, Project Updates, Projects and Centres, Websites and Databases

Tags: Archives, Bess of Hardwick, Digitization, Editions, England, Gender, Materiality, Sixteenth Century, Women

Podcast available on the seminar page!

Podcast available on the seminar page!

Alison fields questions.

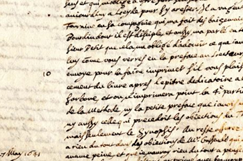

Bess in the 1590s.

Dr Alison Wiggins of the University of Glasgow got our third seminar series off to a brilliant start on 26 April with a sophisticated and thought-provoking presentation on Editing Bess of Hardwick’s Letters Online. As Principal Investigator of the Letters of Bess Hardwick Project (funded by the AHRC), Alison described the benefits and methodological challenges of digitizing this unique Renaissance correspondence, which consists of approximately 245 extant letters (160 to and 85 from Bess) scattered across 18 different repositories spanning a period of nearly 60 years.

Using several examples drawn from the corpus, Alison argued that making all of the letters available in an open-access, fully searchable online edition will enable scholars to pursue a wide range of linguistic, sociological, and historical questions, and will allow them to arrive at a much more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the character of Bess herself, who has been variously depicted as a materialistic virago or as an admirable defender of women’s honour.

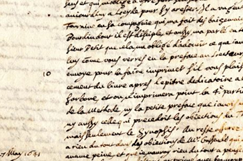

Moving on to more methodological questions, Alison explained that capturing and communicating significant information on the material and visual features of letters, such as the writer’s use of ‘significant space’, paper quality and size, the employment of colourful silk ribbons and flosses, seal choice, and the many varieties of folding, can be particularly difficult in a digital environment, which has a tendency to reify disembodied text at the expense of the letter-object (concerns also raised by Henry Woudhuysen and James Daybell in previous talks). This is a significant problem, since such information is not just antiquarian micro-detail; on the contrary, for contemporary recipients, all of these carefully considered material decisions on the part of the sender conveyed specific social meanings about politeness, deference, and hierarchy which set important parameters for the reception and consumption of a letter’s written content. However, such physical variables and their nuances are not easy to capture faithfully with a simple measurement or colour chart reference in a metadata field. The solutions developed by Alison and her team in the context of the Bess project (such as encoding each of the four recognized kinds of letter-fold − tuck and fold, slit and band, accordion, and sewn − within each letter’s XML to facilitate searching and filtering by plicature and packet type) genuinely move forward thinking in this oft-neglected area and will be of great interest to other digital initiatives.

Moving on to more methodological questions, Alison explained that capturing and communicating significant information on the material and visual features of letters, such as the writer’s use of ‘significant space’, paper quality and size, the employment of colourful silk ribbons and flosses, seal choice, and the many varieties of folding, can be particularly difficult in a digital environment, which has a tendency to reify disembodied text at the expense of the letter-object (concerns also raised by Henry Woudhuysen and James Daybell in previous talks). This is a significant problem, since such information is not just antiquarian micro-detail; on the contrary, for contemporary recipients, all of these carefully considered material decisions on the part of the sender conveyed specific social meanings about politeness, deference, and hierarchy which set important parameters for the reception and consumption of a letter’s written content. However, such physical variables and their nuances are not easy to capture faithfully with a simple measurement or colour chart reference in a metadata field. The solutions developed by Alison and her team in the context of the Bess project (such as encoding each of the four recognized kinds of letter-fold − tuck and fold, slit and band, accordion, and sewn − within each letter’s XML to facilitate searching and filtering by plicature and packet type) genuinely move forward thinking in this oft-neglected area and will be of great interest to other digital initiatives.

Following a brief, appetite-whetting demonstration of the Bess letters alpha software, a lively question and answer session concluded the seminar, which covered such topics as the sociolinguistic significance of employing scribes and the iconographic implications of Bess using her ‘ES’ signature both in letters and as architectural embellishment on her stately home, Hardwick Hall. Broader concerns were also addressed, including the need for digital projects to produce REF-friendly outputs – an increasingly important theme – and ways of ensuring the preservation and accessibility of online resources long after project funding comes to an end. The soon-to-be-released Bess of Hardwick Letters Online will include annotated transcriptions of all of the letters and images of many, as well as articles and podcasts offering further contextual analyses of the correspondence. For news about its release date, stay tuned!

Seminars take place in the Faculty of History on George Street on Thursdays at 3pm. For future talks in the series – and to listen to the podcast of Alison’s paper – please see the seminar webpage. All are welcome!

Dr Penman during his talk.

For the sixth paper of our seminar series on Thursday 9 June, our very own Dr Leigh Penman (University of Oxford) shared some of his most interesting Project findings in a talk entitled ‘How Large was Hartlib’s Archive? A Quantiative Analysis and Comparative Reassessment’. In a richly illustrated and wide-ranging analysis, Penman provided both startling new quantitative insights into the original scope of Hartlib’s correspondence, and a rich narrative explanation of why his epistolary corpus has descended to us in such partial form. In the first half of the paper, Penman described the dimensions and attributes of the extant archive, most of which survives among the holdings of Sheffield University Library (and was previously digitized by the Hartlib Papers Project). He also introduced some brand new Hartlib letters he has located in other international repositories, and used the following algorithm, developed in partnership with a theoretical physicist, to estimate the total extent of the original archive:

For the sixth paper of our seminar series on Thursday 9 June, our very own Dr Leigh Penman (University of Oxford) shared some of his most interesting Project findings in a talk entitled ‘How Large was Hartlib’s Archive? A Quantiative Analysis and Comparative Reassessment’. In a richly illustrated and wide-ranging analysis, Penman provided both startling new quantitative insights into the original scope of Hartlib’s correspondence, and a rich narrative explanation of why his epistolary corpus has descended to us in such partial form. In the first half of the paper, Penman described the dimensions and attributes of the extant archive, most of which survives among the holdings of Sheffield University Library (and was previously digitized by the Hartlib Papers Project). He also introduced some brand new Hartlib letters he has located in other international repositories, and used the following algorithm, developed in partnership with a theoretical physicist, to estimate the total extent of the original archive:

L = S(x/y)

The equation multiplies the sample size (S) by references in the sample to letters no longer extant (x) divided by references in the sample to surviving letters (y) to arrive at the averaged estimate of total correspondence (L); in Hartlib’s case, a grand total of 11,508 letters, a figure large enough to catapult him into the first rank of European intelligencers such as Peiresc, Boulliau, and Leibniz. In the second half of the paper, Penman speculated on why only around 42% of this original corpus has descended to us. In a painstaking reconstruction of the archive’s passage through space and time – and through different ‘microsociologies’, in Penman’s memorable phrase – he described the steady attrition of Hartlib’s papers through thefts and fires while he was still alive; the sale and scattering of papers by his two sons following his death; and the relocation of the papers to Brereton Hall (pictured) in Cheshire around 1664, where they fell prey to the systematic manipulations of John Worthington, William Brereton, and others. He also discussed further archival tampering in the nineteenth century, evidence for which is liberally scattered throughout the papers (for example in the wrappers of the surviving ‘bundles’), as well as in several long-overlooked scholarly articles. Questions focused on the nature of the mathematical calculations; the grey areas between correspondence and other varieties of document in Hartlib’s notoriously difficult archive; the importance of autograph collections and auction catalogues as sources for the reconstruction of nineteenth-century archives; and the curious lack of interest in Hartlib’s work and legacy on the part of early members of the Royal Society. Seminars take place in the Faculty of History on George Street on Thursdays at 3pm. For future talks in the series, please see the seminar webpage.

Podcast now available on the seminar page!

Podcast now available on the seminar page!

James Brown

June 09, 2011

Events, Lectures, Project Updates

Tags: Archives, Communication, England, Materiality, Networks, Politics, Religion, Scribal Copies, Seventeenth Century, Sixteenth Century

In the fifth paper of our seminar series on Thursday 2 June, Professor James Daybell (University of Plymouth) delivered a fascinating paper entitled ‘The Scribal Circulation of Early Modern Letters’. Debuting material from his forthcoming book on the materiality of the letter, and in a slight change from the advertised title, Daybell provided a sophisticated overview of the ‘complex textual afterlives’ of letters beyond their initial composition, sending, and receipt; a conceptualization which challenges prevailing views of early modern epistolarity as a private, historically anchored exchange between only two individuals. By means of a rich range of political and religious examples from early modern England, Daybell traced several consecutive phases of subsequent manuscript dissemination: the controlled circulation of epistolary separates through private copying within discrete manuscript networks; a less discriminate casting abroad; commercial scribal publication within anthologies and miscellanies (in which copies of letters co-mingled with verse, libels, prose, and other manuscript genres); and finally, in many cases, print publication. Daybell also provided insights into the postal conditions which facilitated scribal transmission in early modern England, a surprisingly makeshift mixture of different delivery methods (ordinary posts, royal posts, messengers, carriers, servants, and chance travellers) until the introduction of a more stable and predictable postal structure with the founding of the post office in 1635. Questions focussed on the role of London and the universities as entrepôts for scribal dissemination; the costs of delivery; the anxieties and self-censorship engendered by the instability and porosity of the early modern postal network; and the distinction between ordinary street copies and scribal separates produced by commercial scriptoria. Seminars take place in the Faculty of History on George Street on Thursdays at 3pm. For future talks in the series, please see the seminar webpage.

In the fifth paper of our seminar series on Thursday 2 June, Professor James Daybell (University of Plymouth) delivered a fascinating paper entitled ‘The Scribal Circulation of Early Modern Letters’. Debuting material from his forthcoming book on the materiality of the letter, and in a slight change from the advertised title, Daybell provided a sophisticated overview of the ‘complex textual afterlives’ of letters beyond their initial composition, sending, and receipt; a conceptualization which challenges prevailing views of early modern epistolarity as a private, historically anchored exchange between only two individuals. By means of a rich range of political and religious examples from early modern England, Daybell traced several consecutive phases of subsequent manuscript dissemination: the controlled circulation of epistolary separates through private copying within discrete manuscript networks; a less discriminate casting abroad; commercial scribal publication within anthologies and miscellanies (in which copies of letters co-mingled with verse, libels, prose, and other manuscript genres); and finally, in many cases, print publication. Daybell also provided insights into the postal conditions which facilitated scribal transmission in early modern England, a surprisingly makeshift mixture of different delivery methods (ordinary posts, royal posts, messengers, carriers, servants, and chance travellers) until the introduction of a more stable and predictable postal structure with the founding of the post office in 1635. Questions focussed on the role of London and the universities as entrepôts for scribal dissemination; the costs of delivery; the anxieties and self-censorship engendered by the instability and porosity of the early modern postal network; and the distinction between ordinary street copies and scribal separates produced by commercial scriptoria. Seminars take place in the Faculty of History on George Street on Thursdays at 3pm. For future talks in the series, please see the seminar webpage.

Podcast now available on the seminar page!

Podcast now available on the seminar page!

Erik-Jan points out the stamp which, when viewed under UV light, alerted him to the stolen Libri letter.

The stolen letter on the 'Meditations', discovered by Erik-Jan at Haverford College in 2010.

In the third paper of our seminar series on Thursday 19 May, Dr Erik-Jan Bos (University of Utrecht) gave a talk entitled ‘To the Editor’s Delight: The Loss, Theft, and Forgery of Descartes’ Letters’. In a fascinating and playful analysis, Bos described some of the most outrageous examples of intellectual fraud and finagling he has encountered during his intensive work on the 750-letter corpus. These include the mysterious disappearance of the Stockholm chest in the early 1700s (one of two left to posterity by the French philosopher); omissions, elisions, and other dubious practices by Claude Clerselier, the first editor of the correspondence; the pilfering of around eighty letters by the voracious eighteenth-century manuscript collector Guglielmo Libri (one of which, previously unknown, was discovered by Erik-Jan in Haverford College in 2010); and some sensational and implausible nineteenth-century counterfeits created by forger Denis Vrain-Lucas and sold to the unwitting mathematician and collector Michel Chasles, who proclaimed their authenticity to the French Academy of Science. A lively discussion focused on attempts to reconstruct the contents of the Stockholm chest, the circumstances surrounding Erik-Jan’s discovery of the lost Libri letter in a Pennsylvania library, and the reasons for the surprisingly high percentage of out letters in the Cartesian corpus (570 surviving letters are from him, and only 180 to him). Seminars take place in the Faculty of History on George Street on Thursdays at 3pm. For future talks in the series, please see the seminar webpage.

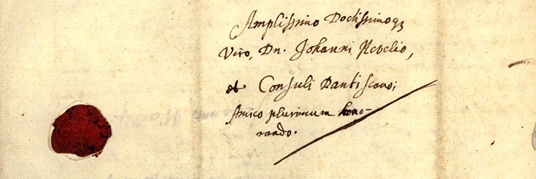

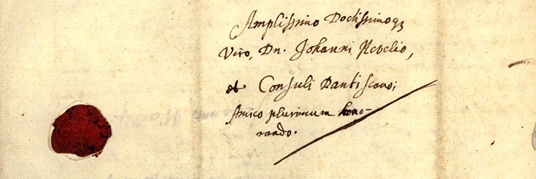

Detail of letter from John Wallis to Jan Hevelius. Oxford, 26 October 1668 (Waller Collection, Uppsala Universitet, Uppsala; Waller MS gb-01783).

In the fourth installment of the Project’s seminar series on Thursday 20 May, Professor Henry Woudhusyen (University College London) examined the material dimensions of epistolary practice in a fascinating paper entitled ‘Writing a Letter in Early Modern England: Forms and Formats’. Arguing that the ‘social life’ (or ‘cultural biography’) of the letter-as-object has attracted little sustained scholarly attention (a trend reinforced by the tendency of online repositories of letters to efface their material attributes), Woudhuysen used a wide range of examples to explore varieties of and markets for paper and ink; handwriting, superscriptions and addresses, salutations, signatures, and ‘significant space’ (those portions of the page left deliberately black for symbolic or practical reasons); the complex relationship between the formatting of letters and economics, in particular in terms of the strategies employed by letter-writers to maximise available space in order to reduce the cost of postage (such as cross-hatching and the forced invasion of margins); and different styles of folding and sealing, and their associated connotations. Woudhusyen’s contribution was further enriched by a commentary from Dr Peter Beal (School of Advanced Study), formerly of Sotheby’s, and the creator of the Catalogue of English Literary Manuscripts (CELM). In a wide-ranging addendum, Beal discussed (inter alia) the cultural transmission of epistolary styles, casting doubt in particular on the ability of prescriptive letter-writing manuals to shed light on these complex processes; considered the relationship between the formatting of letters and that of the other products of early modern scribal culture (such as petitions); and explored the ways in which letters were stored and filed by their recipients. Seminars take place in the Faculty of History on George Street on Thursdays at 3pm. For future seminars in the series, please see here.

Podcast now available on the seminar page!

Podcast now available on the seminar page!

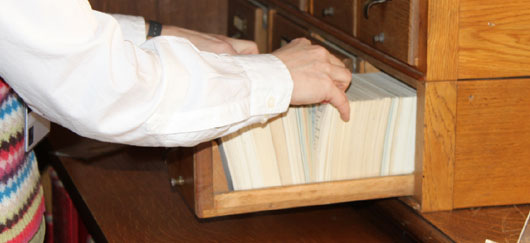

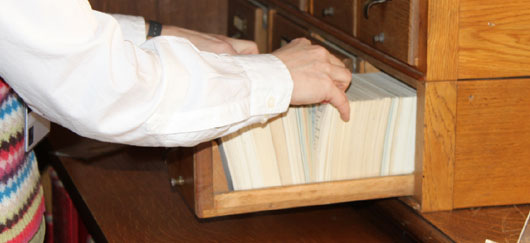

Exploring the hard copy index in the Selden End of Duke Humfreys Library in the Bodleian

We are delighted to announce that Dr Kim McLean-Fiander will be joining the Project as an Editorial Assistant. Kim will be working intensively with the digitized version of the Card Catalogue of MS Correspondence in the Bodleian Library (which will form an initial core of material for our union catalogue of seventeenth-century letters), proofing the keyed texts and bringing them into conformity with Project standards. Her academic research touches upon the intellectual networks of seventeenth-century women, while she has wide-ranging experience of cataloguing and editing at the Bodleian Libraries and at the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington DC. For a full profile see here.

Podcast available on the seminar page!

Moving on to more methodological questions, Alison explained that capturing and communicating significant information on the material and visual features of letters, such as the writer’s use of ‘significant space’, paper quality and size, the employment of colourful silk ribbons and flosses, seal choice, and the many varieties of folding, can be particularly difficult in a digital environment, which has a tendency to reify disembodied text at the expense of the letter-object (concerns also raised by Henry Woudhuysen and James Daybell in previous talks). This is a significant problem, since such information is not just antiquarian micro-detail; on the contrary, for contemporary recipients, all of these carefully considered material decisions on the part of the sender conveyed specific social meanings about politeness, deference, and hierarchy which set important parameters for the reception and consumption of a letter’s written content. However, such physical variables and their nuances are not easy to capture faithfully with a simple measurement or colour chart reference in a metadata field. The solutions developed by Alison and her team in the context of the Bess project (such as encoding each of the four recognized kinds of letter-fold − tuck and fold, slit and band, accordion, and sewn − within each letter’s XML to facilitate searching and filtering by plicature and packet type) genuinely move forward thinking in this oft-neglected area and will be of great interest to other digital initiatives.

Moving on to more methodological questions, Alison explained that capturing and communicating significant information on the material and visual features of letters, such as the writer’s use of ‘significant space’, paper quality and size, the employment of colourful silk ribbons and flosses, seal choice, and the many varieties of folding, can be particularly difficult in a digital environment, which has a tendency to reify disembodied text at the expense of the letter-object (concerns also raised by Henry Woudhuysen and James Daybell in previous talks). This is a significant problem, since such information is not just antiquarian micro-detail; on the contrary, for contemporary recipients, all of these carefully considered material decisions on the part of the sender conveyed specific social meanings about politeness, deference, and hierarchy which set important parameters for the reception and consumption of a letter’s written content. However, such physical variables and their nuances are not easy to capture faithfully with a simple measurement or colour chart reference in a metadata field. The solutions developed by Alison and her team in the context of the Bess project (such as encoding each of the four recognized kinds of letter-fold − tuck and fold, slit and band, accordion, and sewn − within each letter’s XML to facilitate searching and filtering by plicature and packet type) genuinely move forward thinking in this oft-neglected area and will be of great interest to other digital initiatives.

For the sixth paper of our

For the sixth paper of our  In the fifth paper of our

In the fifth paper of our

Join

Join