With its whirl of bunting, teapots, cotton frocks, and the river pageant, Diamond Jubilee fever is sweeping the country for just the second time in British history. Early modern subjects might not have had the opportunity to celebrate a sixty-year reign, but it’s clear from Early Modern Letters Online – itself replete with royalty from across Europe – that they knew how to mark in style royal and aristocratic betrothals, marriages, and birthdays, whilst countrywide celebrations of military victories and triumphant peace treaties helped bolster national unity.

With its whirl of bunting, teapots, cotton frocks, and the river pageant, Diamond Jubilee fever is sweeping the country for just the second time in British history. Early modern subjects might not have had the opportunity to celebrate a sixty-year reign, but it’s clear from Early Modern Letters Online – itself replete with royalty from across Europe – that they knew how to mark in style royal and aristocratic betrothals, marriages, and birthdays, whilst countrywide celebrations of military victories and triumphant peace treaties helped bolster national unity.

Then, as now, cities, towns, and institutions arranged peals of bells, official gun salutes, and lavishly styled river pageants for their inhabitants to enjoy. Eminent speakers delivered orations and sermons from pulpits at moments of national importance – we read how ‘Dr. Sherlock is to preach in St. Pauls before Q.Anne to celebrate the glorys and triumphs of the late victorys in Germany. “You may easily imagine that the D. of M. will have no inconsiderable part in the panegyrie”’. Professional intelligencer John Pory wrote to Sir Robert Cotton in 1607 describing the masque Hymenaei which was designed by Inigo Jones and written by Ben Jonson to celebrate the marriage of Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, and Lady Francis Howard (not that of Prince Henry, as erroneously noted in the abstract). Just as we do today, they enjoyed firework spectaculars; and at the end of the War of the Spanish Succession we find ‘an invitation to the freeholders of Canterbury to partake of a roast ox, bread and beer to celebrate Peace on July 8’ (a service in St Paul’s Cathedral was held also to mark the Peace of Utrecht, at which Handel’s Utrecht Te Deum and Jubilate was given its premiere). As one might expect, bonfires and beacons lit the night sky on numerous occasions and finery was donned for balls and dances, but, in a week during which the highlight here at Cultures of Knowledge has been a paper on the correspondence of James I’s daughter Elizabeth Stuart (podcast to come!), the ‘Winter Queen’ reminds us what’s missing today: scheduled into the festivities that marked her marriage to Frederick, Elector Palatine is the description of a ritual we have lost in these modern celebrations – the tilting match, or joust. Something to suggest to cyclists at the local street party?

Miranda is editing metadata from the Bodleian card catalogue of correspondence for our union catalogue, Early Modern Letters Online. On a regular basis, she brings us hand-picked and contextualised records.

Philip Beeley

May 31, 2012

Events, Lectures, Project Updates

Tags: Astronomy, Editions, Europe, History of Science, Johannes Hevelius, Networks, Seventeenth Century, Theft

On 26 September 1679, while the astronomer Johannes Hevelius and his wife Elizabetha were spending a relaxing evening in gardens outside the gates of their home city of Danzig (Gdańsk), fire consumed their house in the old town. A large part of their possessions, books, personal manuscripts, and instruments, was destroyed; by the following morning the observatory which Hevelius had carefully erected on the roof of the house lay in ruins.

Much was irretrievably lost, but remarkably the letters he had exchanged with the learned men and women of Europe, including Kepler, Boulliau, Gassendi, Christiaan Huygens, Oldenburg, Wallis, and Kircher, together with his treasured collection of Kepler manuscripts, survived. At that time comprising thirteen volumes, the correspondence of Hevelius constitutes one of the great resources for the study and appreciation of early modern scientific networks.

Hevelius’s 45m focal-length telescope.

Johannes Hevelius.

Making this extraordinarily rich corpus available to the wider scholarly community is the task of a major collaborative editorial project currently underway in France, Germany, and Poland, of which I am pleased to be serving on the advisory committee. With most of the over 2,700 surviving letters now housed in collections at the BNF and the Bibliothèque de l’Observatoire in Paris, it was particularly fitting that the director of the French team Professor Chantal Grell (University of Versailles) – accompanied by Professor Robert Halleux (University of Liège) – should inform our third seminar series of the background and methodologies of this ambitious enterprise on Thursday 10 May. In a talk entitled ‘Editing the Correspondence of Johannes Hevelius: Networks, Themes, and Methodological Challenges’, Chantal first provided an overview of Hevelius’s life and letters, before giving a lively account of the complex archival afterlives of the astronomer’s epistolary collection following his death in 1687, including details of the letters famously purloined by Guillaume Libri in the mid-nineteenth century. Following a conspectus of Hevelius’s many correspondents, Chantal concluded with an analysis of the exemplary seventeenth-century scientific exchange between Hevelius and Pierre de Noyers, the secretary to the Queen of Poland. Following an interesting question and answer session – which included, inter alia, discussion of the benefits and challenges of balancing hard copy and digital outputs within large-scale correspondence projects – the evening came to fitting conclusion with a visit to the opening of the Renaissance in Astronomy exhibition at the Museum of the History of Science.

Seminars take place in the Faculty of History on George Street on Thursdays at 3pm. For future talks in the series, please see the seminar webpage. All are welcome!

The neglected theme of epistolary archives – the active collection and curation of letter objects and related papers within various social and institutional ecosystems over broad expanses of time – is close to the heart of Cultures of Knowledge, so we’re delighted to see that friends and colleagues at the Centre for Editing Lives and Letters at QMUL are organizing a fascinating-sounding anniversary conference on The Permissive Archive. To be held at CELL in November 2012, the conference ‘seeks presentations from a wide range of work which opens up archives – not only by bringing to light objects and texts that have lain hidden, but by demystifying and demonstrating the skills needed to make new histories’. Aiming to rescue archives from their persistent but wildly misleading association with neutrality, inertia, and ‘settled dust’, the conference invites proposals (which should cover the period 1500-1800) on definitions of permissive archives; the shape of the archive – ideology and interpretation; the archive which challenges or disrupts; dispersed collections; the archivist and the historian; the ethics and comedy of the archive; order and anarchy; and many more exciting topics.

The deadline for 300-word proposals for 25 minute papers is 31 July 2012. For full details and submission instructions, head along to the conference webpage.

The deadline for 300-word proposals for 25 minute papers is 31 July 2012. For full details and submission instructions, head along to the conference webpage.

James Brown

May 25, 2012

Events, Lectures, Podcasts, Project Updates

Tags: Animals, Conrad Gessner, Felix Platter, History of Science, Illustration, Natural History, Networks, Sixteenth Century

Podcast available on the seminar page!

Podcast available on the seminar page!

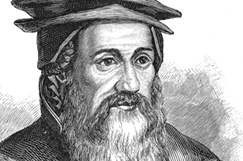

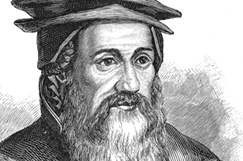

The zoological theme continued on Thursday 3 May when Florike Egmond from Leiden University (formerly of the Clusius Project) gave a talk in our seminar series entitled The Webs of Clusius and Gessner: Correspondence, Images, and Collecting in Sixteenth-Century Natural History. In a detailed and lavishly illustrated discussion, Florike described her recent discovery of two albums of original watercolour drawings created for the sixteenth-century Swiss naturalist Conrad Gessner (1551-1558) within the Special Collections of the University of Amsterdam.

The zoological theme continued on Thursday 3 May when Florike Egmond from Leiden University (formerly of the Clusius Project) gave a talk in our seminar series entitled The Webs of Clusius and Gessner: Correspondence, Images, and Collecting in Sixteenth-Century Natural History. In a detailed and lavishly illustrated discussion, Florike described her recent discovery of two albums of original watercolour drawings created for the sixteenth-century Swiss naturalist Conrad Gessner (1551-1558) within the Special Collections of the University of Amsterdam.

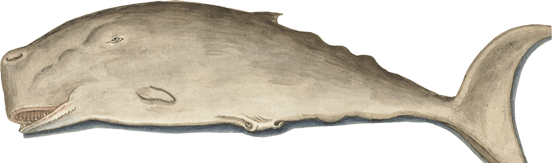

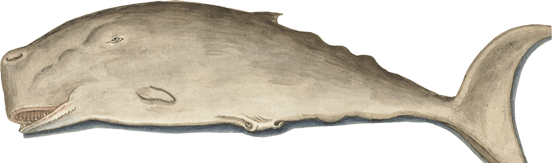

Crafted in Basel by the anatomist and natural historian (and Gessner’s friend) Felix Platter (1536-1614), the images – of a menagerie of marine life, mammals, reptiles, and amphibians, across 369 pages – formed the basis of many of the illustrations within Gessner’s zoological masterwork, the Historiae Animalium (1551-1558). You can find out more about this exciting discovery in Florike’s recent blog post for the Picturing Science network, and in her recent article for the Journal of the History of Collections.

Conrad Gessner.

Anna Marie chairs Florike.

Renaissance correspondence networks, argued Florike, played a key role in sharing and disseminating (although not, curiously, in facilitating discussion of) manuscript images, as both Gessner, Clusius, and other naturalists solicited hand-drawn illustrations of animals to serve as the basis of woodcuts in their publications from colleagues and agents around the world. These exchanges, in turn, formed the basis of what Florike termed (with caveats) a kind of visual ‘canon formation’ within natural history, as elements of various portrayals were adapted, reworked, and reappropriated across different contexts and between media; as representational norms stabilized; and as the repertoire of animals deemed suitable for inclusion in zoological texts (whose wide remit originally encompassed familiar creatures such as cats and goats) was narrowed and standardized. A lively question and answer session focused on the artisanal communities responsible for producing the illustrations; how the works were commissioned and stored; and the frustrating but typical absence of any kind of discussion of manuscript images in the letters with which they circulated (resulting, suggested Florike, from the self-evident nature of enclosed materials).

Seminars take place in the Faculty of History on George Street on Thursdays at 3pm. For future talks in the series – and to listen to the podcast of Florike’s paper – please see the seminar webpage. All are welcome!

James Brown

May 22, 2012

Conferences and Workshops, Events, Project Updates, Projects and Centres

Tags: CKCC, Databases, IMPAcT, ImpulsBauhaus, Mapping the Republic of Letters, Networks, Prosopography, The French Book Trade in Enlightenment Europe, Union Catalogue, Union Catalogue News, Visualization, Wikipedia

While Anna Marie was weaving animal magic at the Royal Society, our Technical Director Neil Jefferies and I were headed to the Forzhungszentrum Gotha of the University of Erfurt for an invited workshop on ‘Visualizing Data Resources: The Potential of a Wikimedia Platform for the Digital Humanities’ (27–28 April 2012). Expertly organised by Martin Mulsow, Olaf Simons, and Kristina Petri, and generously funded by Wikimedia Deutschland – the largest and most active of the national chapters – the workshop provided an inspiring forum for a wide range of international participants and projects to share approaches and converge on the question of Wikipedia, the digital humanities, visualizations, and many points in between (see the full description [pdf]).

One set of presentations showcased the Wikimedia community’s own plans for data capture and computational seeing, many of which have great potential for the digital humanities; not always a straightforward relationship, as Olaf discussed in his opening address. These include Wikidata (a collaboratively curated, centralised database of entities designed to support the 280+ language editions of Wikipedia, as well as third-party initiatives, currently under development), and Semantic Mediawiki, an open source extension to Wikipedia capable of (re)organizing the site’s existing content into highly configurable, collectively editable semantic databases. The accumulation and management of structured, actionable (wiki)data within these streamlined platforms will facilitate the creation and deployment of information visualizations across the site’s many interfaces, and by its millions of users in the context of exports and mash-ups.

Scott Weingart (Indiana/CKCC), Neil (CofK/Oxford), James (CofK/Oxford), and Nicole Coleman (MRofL/Stanford).

Andreas Wolter (ImpulsBauhaus), Jens Weber (ImpulsBauhaus), and Judith Pfeiffer (IMPAcT/Oxford).

A second cluster of talks focused on the data capture, curation, and visualization techniques and applications being pursued and developed by humanistic projects based in archives, libraries, and universities worldwide. As well as presentations from ourselves and good friends Mapping the Republic of Letters, The French Book Trade in Enlightenment Europe, CKCC, IMPAcT, and Scott Weingart, we heard about (inter alia) linked data and gamification at the University of Colorado; an adaptive, interactive, dynamic historical atlas (AIDA) being created at the University of Erfurt; and the wonderful ImpulsBauhaus initiative based at the the Bauhaus-Universität Weimar. Designed to collect information on and represent the global social networks of the Bauhaus, and led by the designer-developer team Jens Weber and Andreas Wolter in 2009, the project harvested extensive biographical and prospopgraphical data on the movement’s participants and affiliates within a specially designed platform which served as the basis for dynamic network infographics and an interactive three-dimensional table, presented most memorably within an illuminated cube. A video of this extraordinary project opens the post.

James Brown

May 14, 2012

Conferences and Workshops, Events, Exhibitions, Podcasts, Project Updates

Tags: Animals, Conchology, Frogs, History of Medicine, History of Science, Illustration, Insects, Martin Lister, Natural History, Ornithology, Royal Society, Seventeenth Century, Toads

Generously sponsored by the project, The Royal Society, The Wellcome Trust, the John Fell Fund, and the BSHS, sixty-three delegates attended the day-long event, which featured papers from eleven international authorities on early modern science. Speakers discussed everything from the views of French naturalists about the differences between dromedaries and camels, to the chequered history of the publication of the cabinet of natural curiosities of Albertus Seba, to the ornithology of Francis Willughby and John Ray and the scientific representation of frogs and toads.

Helen Watt, our Lhwyd researcher.

Perusing the exhibition.

Anna Marie talks to Jill Lewis.

Early modern ornithologies.

There was a concomitant exhibition in the Royal Society’s Marble Hall, also curated by Anna Marie, featuring a display of relevant books from the Society’s collections; highlights were a bear paw clam displayed alongside its illustration by Lister’s daughters in his Historiae Conchyliorum (1692-97), and John Ray’s Historia Plantarum, in which Ray deployed the terms ‘petal’ and ‘pollen’ for the first time. In a further exciting output, Anna Marie will guest edit a special conference issue of Notes and Records of the Royal Society (December 2012) dedicated to the complex interplay between seventeenth-century medicine and natural history. Dovetailing out from Lister’s own contributions, the special issue will consider to what extent practices and technologies of natural history changed between the Renaissance and the seventeenth century, and will explore how the acquisition of knowledge concerning the natural world and new taxonomies affected the perception and treatment of beasts for medical and experimental use.

With its whirl of bunting, teapots, cotton frocks, and the river pageant, Diamond Jubilee fever is sweeping the country for just the second time in British history. Early modern subjects might not have had the opportunity to celebrate a sixty-year reign, but it’s clear from Early Modern Letters Online – itself replete with royalty from across Europe – that they knew how to mark in style royal and aristocratic betrothals, marriages, and birthdays, whilst countrywide celebrations of military victories and triumphant peace treaties helped bolster national unity.

With its whirl of bunting, teapots, cotton frocks, and the river pageant, Diamond Jubilee fever is sweeping the country for just the second time in British history. Early modern subjects might not have had the opportunity to celebrate a sixty-year reign, but it’s clear from Early Modern Letters Online – itself replete with royalty from across Europe – that they knew how to mark in style royal and aristocratic betrothals, marriages, and birthdays, whilst countrywide celebrations of military victories and triumphant peace treaties helped bolster national unity.Letters in Focus with Miranda Lewis

The deadline for 300-word proposals for 25 minute papers is 31 July 2012. For full details and submission instructions, head along to the

The deadline for 300-word proposals for 25 minute papers is 31 July 2012. For full details and submission instructions, head along to the  The

The

In commemoration of the 300th anniversary of the death of

In commemoration of the 300th anniversary of the death of

Join

Join