Cultures of Knowledge Receives Further Grant

Tags: Union Catalogue News

We are delighted to report that Cultures of Knowledge has been awarded a further grant of $758,000 from the Scholarly Communications and Information Technology program of The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, for the period from 1 January 2013 to 31 December 2014.

We are delighted to report that Cultures of Knowledge has been awarded a further grant of $758,000 from the Scholarly Communications and Information Technology program of The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, for the period from 1 January 2013 to 31 December 2014.

While our existing formula of scholarly projects, events, and digital infrastructure will be retained, the centrepiece of our work will now become the further development of our union catalogue of learned correspondence, Early Modern Letters Online:

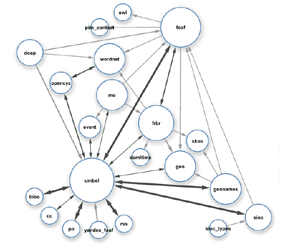

- One task will be to collaborate with a large number of individuals, projects, and repositories beyond Oxford to add significant quantities of new epistolary metadata to EMLO, thereby developing it into an increasingly representative catalogue of the seventeenth-century Republic of Letters.

- A second focus of activity, pursued in partnership with colleagues in Bodleian Digital Library Systems and Services, will be the addition of exciting new features to both the editorial toolset and the discovery interface, designed to transform the catalogue from a finding aid into a genuine tool of research and analysis.

- A focused programme of onboard scholarly projects and events will serve to inform this further phase of systems development, so that it produces editorial and analytical tools closely tailored to the needs of the community of scholars and repositories most engaged in the preservation and study of the epistolary remains of the early modern period.

As we transition to this new phase of activities over the coming months, we will publish these plans in more detail here on the Project website. To receive news of upcoming events and fresh opportunities for collaboration in the meantime, please join the mailing list.

![Caricature, from a South Sea Bubble card. 1720. (Reproduced in Charles Mackay, Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds. [London, 1857], p. 61; image sourced from Wikimedia Commons).](../../../../wp-content/uploads/2012/07/Bubble_Cards.png) As world economies stagger from one crisis to the next and headlines flip-flop between the Eurozone emergency and the scandal of inter-bank lending rate fixing, EMLO provides valuable historical insights into financial turbulence and the effects of similar bubbles and crashes. We may face fresh causes of fiscal breakdown today, but the boom and bust cycle is far from new.

As world economies stagger from one crisis to the next and headlines flip-flop between the Eurozone emergency and the scandal of inter-bank lending rate fixing, EMLO provides valuable historical insights into financial turbulence and the effects of similar bubbles and crashes. We may face fresh causes of fiscal breakdown today, but the boom and bust cycle is far from new. Following on from our participation in a Wikimedia-sponsored data workshop

Following on from our participation in a Wikimedia-sponsored data workshop

Join

Join