You are viewing the Cultures of Knowledge Blog archive for the ‘Lectures’ Category:

James Brown

June 09, 2010

Events, Lectures, Project Updates

Tags: Amsterdam, Antoinette Bourignon, Book History, Communication, Gender, Jan Amos Comenius, Low Countries, Networks, Religion, Seventeenth Century, Women

Discussions continue with Professor de Baar during the wine reception.

In the sixth installment of the Project’s seminar series on Thursday 3 June, Professor Mirjam de Baar (University of Groningen) described the epistolary practice and strategies of a seventeenth-century female prophet and mystic in a paper entitled ‘The Re-construction of a Spiritual Network: The Correspondence of Antoinette Bourignon (1616-1680)’. From her base in Amsterdam (where she purchased her own press in the late 1660s), Bourignon used a variety of textual media to disseminate the message that she was a spiritual leader – ‘The Mother’ – chosen by God to restore true Christianity on earth, and to consolidate a following around this ecumenical identity. Bourignon’s letters, argued de Baar, were central to this programme; over 600 manuscript versions survive (both originals and scribal copies), eleven different printed editions appeared during her lifetime, while nine further volumes were subsequently published posthumously. Her correspondents included luminaries such as Jan Amos Comenius (1592-1670), Robert Boyle (1627-1691), Jan Swammerdam (1637-80), and Pierre Poiret (1646-1719), as well as a wide range of socially diverse disciples who wrote to her seeking advice on a variety of spiritual and personal issues, and whose preoccupations and voices are anonymously reproduced in published responses. In consequence, her letters have a dialogic, polyphonous quality, while the same followers who wrote to her seeking guidance in turn represented an important market for the letters in their printed manifestations, suggesting a close relationship between epistolarity and the mechanics of early modern publishing, and the existence of a shrewd business model beneath the spiritual discourse (a point further underlined during subsequent discussion). Despite her failure to establish a long-term community on the island of Nordstrand, and the fact that in the later years of her life the suspicions of Lutheran clergy forced her into exile in Eastern Friesland, Bourignon maintained a prolific output of letters, and continued to combine the roles of spiritual leader, publisher of epistolary collections, and manager of what might be interpreted as a spiritually driven commercial enterprise. Seminars take place in the Faculty of History on George Street on Thursdays at 3pm. For future seminars in the series, please see here.

Podcast now available on the seminar page!

Podcast now available on the seminar page!

James Brown

June 03, 2010

Events, Lectures, Project Updates

Tags: Amerigo Salvetti, Britain, Diplomatic History, English Civil War, Italy, Politics, Protectorate, Seventeenth Century, Tuscany

In the fifth installment of the Project’s seminar series on Thursday 27 May, Professor Stefano Villani (University of Pisa) introduced us to ‘Tuscan Readings of the English Revolution: The Correspondence of Amerigo Salvetti and Giovanni Salvetti Antelminelli’. Villani focused on the communications sent by the elder Salvetti, a Tuscan informer and diplomat based in London, to the Grand Duke of Tuscany between 1649 and 1660, during which the former dispatched both a newsletter and a personal letter on a weekly basis updating the Tuscan court on developments within the new English Republic. Villani argued that within an environment in which Italian responses to the Protectorate regime were both highly regionalized and lacking in ideological consistency, the letters reveal Tuscans to have had more interest in and sympathy for the Cromwellian administration than either Venetians (who regarded it as a military dictatorship orchestrated by a religious fanatic) or Genoans (who viewed it ambivalently as a kind of protracted Machievellian experiment). As well as describing this ‘Anglo/Tuscan moment’, Villani sketched some fascinating differences between the two styles of missive – newsletter and personal letter – both of which took over a month to reach their recipients on the peninsula. The newsletters, which are anonymous and unsigned, provide a ‘pragmatic’ third person narrative of political events free of subjective judgements and commentaries (and often enclosing translations of English documents). The personal letters, by contrast, are written in the first person, sometimes in cipher, and signed, and contain many idiosyncratic political insights as well as numerous personal references. Seminars take place in the Faculty of History on George Street on Thursdays at 3pm. For future seminars in the series, please see here.

Podcast now available on the seminar page!

Podcast now available on the seminar page!

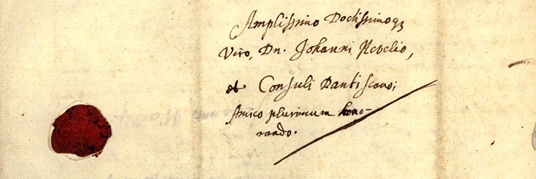

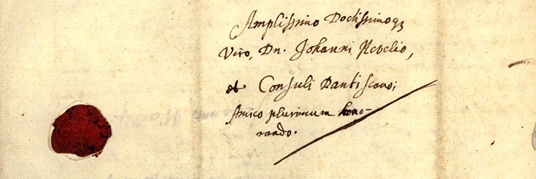

Detail of letter from John Wallis to Jan Hevelius. Oxford, 26 October 1668 (Waller Collection, Uppsala Universitet, Uppsala; Waller MS gb-01783).

In the fourth installment of the Project’s seminar series on Thursday 20 May, Professor Henry Woudhusyen (University College London) examined the material dimensions of epistolary practice in a fascinating paper entitled ‘Writing a Letter in Early Modern England: Forms and Formats’. Arguing that the ‘social life’ (or ‘cultural biography’) of the letter-as-object has attracted little sustained scholarly attention (a trend reinforced by the tendency of online repositories of letters to efface their material attributes), Woudhuysen used a wide range of examples to explore varieties of and markets for paper and ink; handwriting, superscriptions and addresses, salutations, signatures, and ‘significant space’ (those portions of the page left deliberately black for symbolic or practical reasons); the complex relationship between the formatting of letters and economics, in particular in terms of the strategies employed by letter-writers to maximise available space in order to reduce the cost of postage (such as cross-hatching and the forced invasion of margins); and different styles of folding and sealing, and their associated connotations. Woudhusyen’s contribution was further enriched by a commentary from Dr Peter Beal (School of Advanced Study), formerly of Sotheby’s, and the creator of the Catalogue of English Literary Manuscripts (CELM). In a wide-ranging addendum, Beal discussed (inter alia) the cultural transmission of epistolary styles, casting doubt in particular on the ability of prescriptive letter-writing manuals to shed light on these complex processes; considered the relationship between the formatting of letters and that of the other products of early modern scribal culture (such as petitions); and explored the ways in which letters were stored and filed by their recipients. Seminars take place in the Faculty of History on George Street on Thursdays at 3pm. For future seminars in the series, please see here.

Podcast now available on the seminar page!

Podcast now available on the seminar page!

Portrait of Francis Bacon, Viscount St Alban, by John Vanderbank (after an unknown artist). 1713? (c.1618). Oil on canvas, 76.5 by 63.2cm. (National Portrait Gallery, London, NPG520; image taken from Wikimedia Commons).

In the third installment of the Project’s seminar series on Thursday 13 May, Professor Alan Stewart (Columbia University and the Centre for Editing Lives and Letters, QMUL) gave a fascinating and wide-ranging talk on ‘Writing Francis Bacon’s Letters’. Taking as his starting point the curious anomaly that, despite his standing as a public intellectual, Bacon’s own extant letters (c.800) do not address scholarly themes and were not exchanged with continental luminaries such as Galileo, Grotius, and Peiresc (instead focusing on a ‘worldly and slightly sordid narrative’ of social and political affairs), Stewart argued that for an epistolary elaboration of Bacon’s intellectual agenda we need to focus on the letters he crafted as a lawyer and junior parliamentarian on behalf of Robert Devereux (the 2nd Earl of Essex) during the 1590s. Within an environment of manuscript production in which letters were not a private ‘conversation between two absent persons’ (in the Erasmian formulation) but were instead drafted, disseminated, and consumed collaboratively, and a political one in which Essex relied on a large team of quasi-scholarly secretaries and advisers to generate key documentation, Bacon was able to use the letters to advance anonymously themes which prefigure his later The Advancement of Learning (1605). This tactic is particularly evident in a letter ostensibly from Essex to Fulke Greville on research methods (which include Baconian attacks on the usefulness of epitomes and veneration of the value of history), and three letters to Roger Manners, the 5th Earl of Rutland (which include a Baconian discourse on the pursuit of knowledge as the purpose of travel). However, concluded Stewart, scrutiny of these practices during the 1601 trial following Essex’s failed rebellion led Bacon to distrust epistolary formats, meaning that thereafter we must look beyond letters to recontruct his intellectual project. Seminars take place in the Faculty of History on George Street on Thursdays at 3pm. For future seminars in the series, please see here.

Podcast now available on the seminar page!

Podcast now available on the seminar page!

A lecture by Jacob Soll on ‘Enlightenment Libraries and the Quest for Universal Knowledge Reconsidered’ will take place at 3pm on Tuesday 25 May in the Seminar Room of the New Bodleian Library. Soll gained his doctorate in history at Cambridge University after completing a diploma of advanced studies at the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales in Paris. His 2005 book, Publishing The Prince, about the afterlife and translations of Machiavelli’s work, won the Jacques Barzun Prize in Cultural History. Since then he has written about the birth of information culture in Europe, including research on the origins of state archives, on note-taking by early modern readers, on accountancy in seventeenth-century Holland, and the critical uses of historical evidence in early modern Europe. In 2009 he published The Information Master: Jean-Baptiste Colbert’s Secret State Intelligence System. Soll teaches at Rutgers University, New Jersey. He is a Consulting Editor of the Journal of the History of Ideas and a co-founder and Associate Editor of the new online journal Republics of Letters, founded at Stanford University with Dan Edelstein.

A lecture by Jacob Soll on ‘Enlightenment Libraries and the Quest for Universal Knowledge Reconsidered’ will take place at 3pm on Tuesday 25 May in the Seminar Room of the New Bodleian Library. Soll gained his doctorate in history at Cambridge University after completing a diploma of advanced studies at the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales in Paris. His 2005 book, Publishing The Prince, about the afterlife and translations of Machiavelli’s work, won the Jacques Barzun Prize in Cultural History. Since then he has written about the birth of information culture in Europe, including research on the origins of state archives, on note-taking by early modern readers, on accountancy in seventeenth-century Holland, and the critical uses of historical evidence in early modern Europe. In 2009 he published The Information Master: Jean-Baptiste Colbert’s Secret State Intelligence System. Soll teaches at Rutgers University, New Jersey. He is a Consulting Editor of the Journal of the History of Ideas and a co-founder and Associate Editor of the new online journal Republics of Letters, founded at Stanford University with Dan Edelstein.

James Ussher, Archbishop of Armagh and Primate of All Ireland (1581-1656). Wikimedia Commons.

In the second installment of the Project’s seminar series on Thursday 6 May, Dr Elizabethanne Boran (The Edward Worth Library, Dublin, and formerly The Ussher Project) provided another capacity audience with a detailed paper entitled ‘“Live and speak unto the Church, when you are dead”: The Correspondence of James Ussher (1581-1656) and Samuel Ward (1572-1643)’. Focusing on the letters exchanged between the Irish primate and the Master of Sidney Sussex College Cambridge from 1625 – a corpus of around 45 extant documents – Boran used the correspondence to shed fascinating light on the religious preoccupations and perspectives of the two scholars (the letters frequently cover church history, doctrinal controversies, religious radicals, and Arminianism), as well as their unequal personal dynamics (Ussher, the younger but more senior of the two, frequently adopts a superior tone). The paper also used the Ussher/Ward case study as the basis for many suggestive insights into the structure and functioning of correspondence networks more generally, in particular regarding the ‘temporal flow’ of the seventeenth-century Republic of Letters (the rhythm of which was heavily influenced by the seasons and the weather), the complex relationship between the content of correspondence and the itineraries of the senders and receivers as well as their opportunities for verbal forms of contact (letters sent during 1626, when both men were in close physical proximity, are generally ‘staccato’), and the extent to which epistolary networks were mapped onto and relied upon adjacent professional, social, and economic modes of exchange (in particular mercantile and friendship networks, and practices of academic visiting). Seminars take place in the Faculty of History on George Street on Thursdays at 3pm. For future seminars in the series, please see here.

Podcast now available on the seminar page!

Join

Join