Dr Penman during his talk.

For the sixth paper of our seminar series on Thursday 9 June, our very own Dr Leigh Penman (University of Oxford) shared some of his most interesting Project findings in a talk entitled ‘How Large was Hartlib’s Archive? A Quantiative Analysis and Comparative Reassessment’. In a richly illustrated and wide-ranging analysis, Penman provided both startling new quantitative insights into the original scope of Hartlib’s correspondence, and a rich narrative explanation of why his epistolary corpus has descended to us in such partial form. In the first half of the paper, Penman described the dimensions and attributes of the extant archive, most of which survives among the holdings of Sheffield University Library (and was previously digitized by the Hartlib Papers Project). He also introduced some brand new Hartlib letters he has located in other international repositories, and used the following algorithm, developed in partnership with a theoretical physicist, to estimate the total extent of the original archive:

For the sixth paper of our seminar series on Thursday 9 June, our very own Dr Leigh Penman (University of Oxford) shared some of his most interesting Project findings in a talk entitled ‘How Large was Hartlib’s Archive? A Quantiative Analysis and Comparative Reassessment’. In a richly illustrated and wide-ranging analysis, Penman provided both startling new quantitative insights into the original scope of Hartlib’s correspondence, and a rich narrative explanation of why his epistolary corpus has descended to us in such partial form. In the first half of the paper, Penman described the dimensions and attributes of the extant archive, most of which survives among the holdings of Sheffield University Library (and was previously digitized by the Hartlib Papers Project). He also introduced some brand new Hartlib letters he has located in other international repositories, and used the following algorithm, developed in partnership with a theoretical physicist, to estimate the total extent of the original archive:

L = S(x/y)

The equation multiplies the sample size (S) by references in the sample to letters no longer extant (x) divided by references in the sample to surviving letters (y) to arrive at the averaged estimate of total correspondence (L); in Hartlib’s case, a grand total of 11,508 letters, a figure large enough to catapult him into the first rank of European intelligencers such as Peiresc, Boulliau, and Leibniz. In the second half of the paper, Penman speculated on why only around 42% of this original corpus has descended to us. In a painstaking reconstruction of the archive’s passage through space and time – and through different ‘microsociologies’, in Penman’s memorable phrase – he described the steady attrition of Hartlib’s papers through thefts and fires while he was still alive; the sale and scattering of papers by his two sons following his death; and the relocation of the papers to Brereton Hall (pictured) in Cheshire around 1664, where they fell prey to the systematic manipulations of John Worthington, William Brereton, and others. He also discussed further archival tampering in the nineteenth century, evidence for which is liberally scattered throughout the papers (for example in the wrappers of the surviving ‘bundles’), as well as in several long-overlooked scholarly articles. Questions focused on the nature of the mathematical calculations; the grey areas between correspondence and other varieties of document in Hartlib’s notoriously difficult archive; the importance of autograph collections and auction catalogues as sources for the reconstruction of nineteenth-century archives; and the curious lack of interest in Hartlib’s work and legacy on the part of early members of the Royal Society. Seminars take place in the Faculty of History on George Street on Thursdays at 3pm. For future talks in the series, please see the seminar webpage.

Podcast now available on the seminar page!

Podcast now available on the seminar page!

James Brown

June 09, 2011

Events, Lectures, Project Updates

Tags: Archives, Communication, England, Materiality, Networks, Politics, Religion, Scribal Copies, Seventeenth Century, Sixteenth Century

In the fifth paper of our seminar series on Thursday 2 June, Professor James Daybell (University of Plymouth) delivered a fascinating paper entitled ‘The Scribal Circulation of Early Modern Letters’. Debuting material from his forthcoming book on the materiality of the letter, and in a slight change from the advertised title, Daybell provided a sophisticated overview of the ‘complex textual afterlives’ of letters beyond their initial composition, sending, and receipt; a conceptualization which challenges prevailing views of early modern epistolarity as a private, historically anchored exchange between only two individuals. By means of a rich range of political and religious examples from early modern England, Daybell traced several consecutive phases of subsequent manuscript dissemination: the controlled circulation of epistolary separates through private copying within discrete manuscript networks; a less discriminate casting abroad; commercial scribal publication within anthologies and miscellanies (in which copies of letters co-mingled with verse, libels, prose, and other manuscript genres); and finally, in many cases, print publication. Daybell also provided insights into the postal conditions which facilitated scribal transmission in early modern England, a surprisingly makeshift mixture of different delivery methods (ordinary posts, royal posts, messengers, carriers, servants, and chance travellers) until the introduction of a more stable and predictable postal structure with the founding of the post office in 1635. Questions focussed on the role of London and the universities as entrepôts for scribal dissemination; the costs of delivery; the anxieties and self-censorship engendered by the instability and porosity of the early modern postal network; and the distinction between ordinary street copies and scribal separates produced by commercial scriptoria. Seminars take place in the Faculty of History on George Street on Thursdays at 3pm. For future talks in the series, please see the seminar webpage.

In the fifth paper of our seminar series on Thursday 2 June, Professor James Daybell (University of Plymouth) delivered a fascinating paper entitled ‘The Scribal Circulation of Early Modern Letters’. Debuting material from his forthcoming book on the materiality of the letter, and in a slight change from the advertised title, Daybell provided a sophisticated overview of the ‘complex textual afterlives’ of letters beyond their initial composition, sending, and receipt; a conceptualization which challenges prevailing views of early modern epistolarity as a private, historically anchored exchange between only two individuals. By means of a rich range of political and religious examples from early modern England, Daybell traced several consecutive phases of subsequent manuscript dissemination: the controlled circulation of epistolary separates through private copying within discrete manuscript networks; a less discriminate casting abroad; commercial scribal publication within anthologies and miscellanies (in which copies of letters co-mingled with verse, libels, prose, and other manuscript genres); and finally, in many cases, print publication. Daybell also provided insights into the postal conditions which facilitated scribal transmission in early modern England, a surprisingly makeshift mixture of different delivery methods (ordinary posts, royal posts, messengers, carriers, servants, and chance travellers) until the introduction of a more stable and predictable postal structure with the founding of the post office in 1635. Questions focussed on the role of London and the universities as entrepôts for scribal dissemination; the costs of delivery; the anxieties and self-censorship engendered by the instability and porosity of the early modern postal network; and the distinction between ordinary street copies and scribal separates produced by commercial scriptoria. Seminars take place in the Faculty of History on George Street on Thursdays at 3pm. For future talks in the series, please see the seminar webpage.

Podcast now available on the seminar page!

Podcast now available on the seminar page!

Dr van Romburgh during her talk.

Junius's 'Observationes' from 1655.

In the fourth paper of our seminar series on Thursday 26 May, Dr Sophie van Romburgh (University of Leiden) spoke about ‘Reciprocal Bonds Between Words and Friends, or Correspondence According to Francis Junius’. In a poetic and suggestive analysis, van Romburgh outlined a new framework for appreciating the correspondence of the seventeenth-century philologist, which she edited in 2002, by turning to the closely related genre of commentary (the etymological elucidations of words and concepts in early modern source texts). Van Romburgh argued for a comparable set of ‘discursive dynamics’ between commentary and learned correspondence, and suggested that both attempted to add ‘lustre’ to objective, impersonal, abstract knowledge by embedding it within lived experience and wider networks of words, scholars, and friends. Not only does the thematic eclecticism and ‘easy mix’ of classical, biblical, and contemporary voices evident in Junius’s commentaries evoke the lively, promiscuous character of intellectual correspondence, but they also combine serious etymological pursuit with personal anecdote (especially evident in his ‘Observationes’ from 1655). This connects the ‘formal grid’ of the dictionary or source text with broader ‘constellations of knowledge and people’, relating the exotic and the arcane to the familiar and the experiential, and providing an example of early modern ‘associative rhetoric’ (Roberta Frank) in action. Junius’s commentaries also reference extra-textual conversations with scholar-friends, as do his letters; a powerful reminder that both commentary and correspondence existed within a voice-oriented culture (or ‘oral story world’), and superimposed a ‘vast, living world of spoken communication, of which only some glimpses make it to paper’. Cultures of Knowledge, argued van Romburgh, are created within this vast multi-dimensional space, and out of the lived practices of networks of scholar-friends (‘the ecology of early modern scholarship’). Questions focussed on national differences in discursive and communicative cultures; the social and political, as well as the discursive and intellectual, logic of early modern annotations; the pedagogical origins of associational thinking; and the very different historiographical trajectories described by the history of science and the history of scholarship. Seminars take place in the Faculty of History on George Street on Thursdays at 3pm. For future talks in the series, please see the seminar webpage.

Podcast now available on the seminar page!

Podcast now available on the seminar page!

Erik-Jan points out the stamp which, when viewed under UV light, alerted him to the stolen Libri letter.

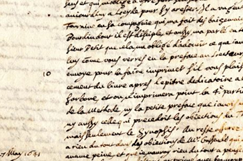

The stolen letter on the 'Meditations', discovered by Erik-Jan at Haverford College in 2010.

In the third paper of our seminar series on Thursday 19 May, Dr Erik-Jan Bos (University of Utrecht) gave a talk entitled ‘To the Editor’s Delight: The Loss, Theft, and Forgery of Descartes’ Letters’. In a fascinating and playful analysis, Bos described some of the most outrageous examples of intellectual fraud and finagling he has encountered during his intensive work on the 750-letter corpus. These include the mysterious disappearance of the Stockholm chest in the early 1700s (one of two left to posterity by the French philosopher); omissions, elisions, and other dubious practices by Claude Clerselier, the first editor of the correspondence; the pilfering of around eighty letters by the voracious eighteenth-century manuscript collector Guglielmo Libri (one of which, previously unknown, was discovered by Erik-Jan in Haverford College in 2010); and some sensational and implausible nineteenth-century counterfeits created by forger Denis Vrain-Lucas and sold to the unwitting mathematician and collector Michel Chasles, who proclaimed their authenticity to the French Academy of Science. A lively discussion focused on attempts to reconstruct the contents of the Stockholm chest, the circumstances surrounding Erik-Jan’s discovery of the lost Libri letter in a Pennsylvania library, and the reasons for the surprisingly high percentage of out letters in the Cartesian corpus (570 surviving letters are from him, and only 180 to him). Seminars take place in the Faculty of History on George Street on Thursdays at 3pm. For future talks in the series, please see the seminar webpage.

Post edited to add photographs

Post edited to add photographs

A lecture by our Martin Lister Research Fellow Dr Anna Marie Roos on ‘The Art of Science: The ‘Rediscovery’ of Martin Lister’s Historiae Conchyliorum (1685-92)’ will take place at 5pm on Tuesday 31 May in the Hawkins Room of Merton College. The event is a joint meeting of the Merton Biomedical and Life Sciences and History of the Book research groups. Anna Marie is a leading authority on the history of science and medicine in early modern England. Alongside her work for Cultures of Knowledge (for which she is editing Lister’s correspondence), she has published widely in the history of chemistry, as well as on magic and astrological medicine. Her talk will focus on the stunning series of copperplates created by Lister’s teenage daughters to illustrate his groundbreaking compendium of shells, the rediscovery of which last year aroused a great deal of interest.

Anna Marie during her talk.

Listerian material from Merton’s holdings.

Update: Deadline extended to 18 October

Update: Deadline extended to 18 October

Paper and panel proposals are invited for Scientiae, a new interdisciplinary conference on early modern science, to be held in Vancouver, B.C. (under the auspices of Simon Fraser University) on 26–28 April 2012. According to the organizers, ‘[t]he working assumption of the conference is that interdisciplinarity is not only an option, but a necessity, for the study of early modern culture in its knowledge of the natural world. That is because period science is itself an interdisciplinary function, emerging from Biblical exegesis, advanced design, and literary humanitas; as well as from natural philosophy, alchemy, craft traditions, etc… Scientiae offers a forum for scholars of the period’s art and literature, as well as its intellectual history, to illuminate aspects of early modern science in the latter’s proper strangeness’. The deadline for proposals is 30 September 2011. For the full CFP, please visit the conference website.

For the sixth paper of our seminar series on Thursday 9 June, our very own Dr Leigh Penman (University of Oxford) shared some of his most interesting Project findings in a talk entitled ‘How Large was Hartlib’s Archive? A Quantiative Analysis and Comparative Reassessment’. In a richly illustrated and wide-ranging analysis, Penman provided both startling new quantitative insights into the original scope of Hartlib’s correspondence, and a rich narrative explanation of why his epistolary corpus has descended to us in such partial form. In the first half of the paper, Penman described the dimensions and attributes of the extant archive, most of which survives among the holdings of Sheffield University Library (and was previously digitized by the Hartlib Papers Project). He also introduced some brand new Hartlib letters he has located in other international repositories, and used the following algorithm, developed in partnership with a theoretical physicist, to estimate the total extent of the original archive:

For the sixth paper of our seminar series on Thursday 9 June, our very own Dr Leigh Penman (University of Oxford) shared some of his most interesting Project findings in a talk entitled ‘How Large was Hartlib’s Archive? A Quantiative Analysis and Comparative Reassessment’. In a richly illustrated and wide-ranging analysis, Penman provided both startling new quantitative insights into the original scope of Hartlib’s correspondence, and a rich narrative explanation of why his epistolary corpus has descended to us in such partial form. In the first half of the paper, Penman described the dimensions and attributes of the extant archive, most of which survives among the holdings of Sheffield University Library (and was previously digitized by the Hartlib Papers Project). He also introduced some brand new Hartlib letters he has located in other international repositories, and used the following algorithm, developed in partnership with a theoretical physicist, to estimate the total extent of the original archive:Podcast now available on the seminar page!

In the fifth paper of our

In the fifth paper of our

Update: Deadline extended to 18 October

Update: Deadline extended to 18 October

Join

Join